85–90% of Primary Liver Cancers Are Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Why Aren’t We Catching It Sooner?

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” -Benjamin Franklin

This rings especially true in medicine, where early detection can mean the difference between life and death. One of the clearest examples of the benefits of early detection in medicine is HepatoCellular Carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of primary liver cancer.[1]

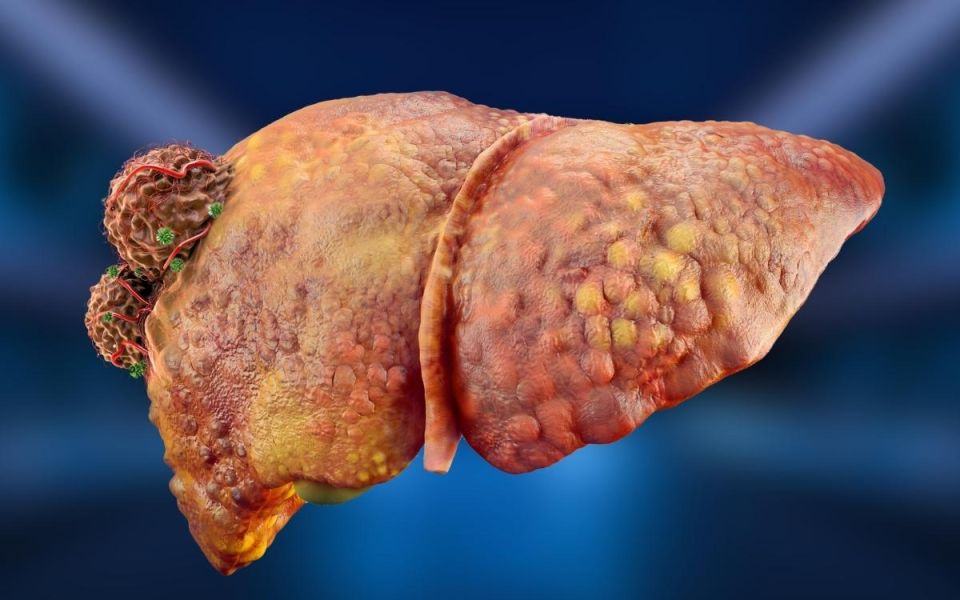

Hepatocellular carcinoma originates in hepatocytes, the main functional cells of the liver. It makes up 85-90% of cancer cases that originate in the liver itself, though other forms of cancer can spread to the liver (called metastases).[1,2] HCC is particularly worrying because rates of many cancers are declining, but liver cancer rates have been rising rapidly in some regions, especially among women.[3,4,5] Men are still more likely to have HCC than women.[3,5] What makes this disease especially dangerous is that most people don’t know they have it until it’s too advanced for our best therapies to offer a reliable cure.[2,6,7]

In hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatocyte liver cells mutate to develop traits that enable them to survive at the expense of the liver and the body. They multiply uncontrollably, resist death, avoid immune system detection, build extra blood vessels to sustain their growth, and spread to other parts of the body.[8] These mutations are genetic, occurring when DNA in liver cells is damaged, and occur with liver damage, especially cirrhosis.[7] As the rogue hepatocytes reproduce, they accumulate and form a mass, called a tumor, that can double in size every 4-5 months, on average.[9]

Cirrhosis is by far the biggest risk factor for developing hepatocellular carcinoma. 80-95% of HCC patients have cirrhosis, and 2-4% of people with cirrhosis develop HCC each year.[2,5,7] Conditions that cause cirrhosis are therefore risks for developing HCC: chronic hepatitis B and C infection, alcoholic fatty liver disease, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH, formerly known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis).[2,7]

Hepatocellular carcinoma has one of the highest mortality rates among types of cancer.[3] Despite half a century of research, which has dramatically improved the 5-year survival rate from 5% in 1977 to 22% in 2020, the disease is often detected too late.[3,4] Think of it like having a hole in your boat; it’s okay if you can plug it early, but the longer you wait, the more trouble you’re in. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases survivability by roughly 300%.[3,2,6]

When detected early enough, doctors can perform potentially curative treatments, including surgery to remove a tumor or liver transplant.[4] These treatments significantly increase the chances of survival, although they are only effective before the disease has spread too far.[4] Researchers have developed techniques for treating later stages of the disease, including targeting the tumors with local radiation, destroying the arteries that supply blood to tumors, and medications that target the tumors’ ability to grow, proliferate, and avoid the immune system.[4,7] These medications deserve a lot of praise for helping increase survival, even though advanced stages of HCC still resist traditional radiation and chemotherapy.[7] The knowledge from early detection remains our most important tool.[7]

Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma requires surveillance. Surveillance is when doctors actively monitor at-risk individuals before symptoms appear. At-risk patients include those with liver cirrhosis, advanced fibrosis, and high-risk diseases like hepatitis B and C.[5] Surveillance unequivocally increases survival rates by detecting tumors while they are still treatable.[5,6]

Current primary surveillance methods include ultrasound and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood tests taken every 6 to 12 months.[2,5] CT scans and MRIs may produce higher false-positive rates, but can still be useful.[2] Unfortunately, even with our best current methods of surveillance, screening identifies fewer than half of HCC patients.[6] Dr. Bharat Misra of ENCORE Borland Groover Clinical Research states:

Despite following the current guidelines of ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein every six months, all of us have encountered patients who have developed advanced HepatoCellular Carcinoma (HCC). There is a definite need for better blood based markers that can detect HCC when it is curable.

Clinical research is investigating new detection methods that will hopefully provide better surveillance. We also need more widespread use of screening methods, and better awareness for those at risk. If you match the risk factors of advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, consider talking to your doctor today about screening for this dangerous disease or joining a clinical research study to make a difference. The ounce of surveillance taken today may be able to cure the three-pound liver of tomorrow.

Creative Director Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

Contributing Author Bharat Misra, MD

|

Click Below for ENCORE Research Group's Enrolling Studies |

|

Click Below for Flourish Research's Enrolling Studies |

References:

[1] Koren, M.J. & Kapila, N. (Hosts). (2025). The liver: Common causes of complications, cirrhosis, and cancer. [Podcast Episode]. In MedEvidence! Truth Behind the Data. MedEvidence. https://www.buzzsprout.com/1926091/episodes/17268919

[2] El-Serag, H. B., & Davila, J. A. (2011). Surveillance for HepatoCellular Carcinoma: in whom and how?. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology, 4(1), 5-10. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1756283X10385964

[3] Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H., & Jemal, A. (2025). Cancer statistics, 2025. Ca, 75(1), 10. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21871

[4] Benson, A. B., D’Angelica, M. I., Abbott, D. E., Anaya, D. A., Anders, R., Are, C., ... & Darlow, S. D. (2021). Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 19(5), 541-565. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/19/5/article-p541.xml

[5] Heimbach, J. K., Kulik, L. M., Finn, R. S., Sirlin, C. B., Abecassis, M. M., Roberts, L. R., ... & Marrero, J. A. (2018). AASLD guidelines for the treatment of HepatoCellular Carcinoma. Hepatology, 67(1), 358-380.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28130846/

[6] Singal, A. G., Mittal, S., Yerokun, O. A., Ahn, C., Marrero, J. A., Yopp, A. C., ... & Scaglione, S. J. (2017). HepatoCellular Carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. The American journal of medicine, 130(9), 1099-1106. https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(17)30128-6/fulltext

[7] Llovet, J. M., Pinyol, R., Kelley, R. K., El-Khoueiry, A., Reeves, H. L., Wang, X. W., ... & Villanueva, A. (2022). Molecular pathogenesis and systemic therapies for HepatoCellular Carcinoma. Nature cancer, 3(4), 386-401. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-022-00357-2

[8] Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2000). The hallmarks of cancer. Cell, 100(1), 57-70.https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(00)81683-9

[9] Nathani, P., Gopal, P., Rich, N., Yopp, A., Yokoo, T., John, B., ... & Singal, A. G. (2021). HepatoCellular Carcinoma tumour volume doubling time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut, 70(2), 401-407. https://gut.bmj.com/content/70/2/401.abstract